NAME: Abra

TRACK: Pull Up

YEAR: 2016

FROM: USA

Author: madamerap

070 Shake

NAME: 070 Shake

TRACK: Trust Nobody

YEAR: 2016

FROM: New Jersey, USA

Tange Lomax

NAME: Tange Lomax

TRACK: Big Dawg

YEAR: 2016

FROM: USA

Bali Baby

NAME: Bali Baby

TRACK: Do Da Dash

YEAR: 2016

FROM: Atlanta, USA

Jaylii

NAME: Jaylii

TRACK: Hunnits

YEAR: 2016

FROM: USA

Katastrophe

NAME: Katastrophe

TRACK: Let Me Go

YEAR: 2012

FROM: San Francisco, USA

MC Zuzka

NOM : MC Zuzka

TITRE : Proti Všem Děvkám

ANNÉE : 2014

PAYS : Tchéquie

Sharkass

NAME: Sharkass

TRACK: Nevrátím

YEAR: 2013

FROM: Czechia

Lara 303

NAME: Lara 303

TRACK: Revoluce

YEAR: 2012

FROM: Czechia

Poetikiss

NAME: Poetikiss

TRACK: Song in 60 seconds: Mood

YEAR: 2016

FROM: USA

Lejdi Ledi

NAME: Lejdi Ledi

TRACK: Ja Sam

YEAR: 2012

FROM: Serbia

Flash Marley

NAME: Flash Marley

TRACK: Eponyme

YEAR: 2016

FROM: Lomé, Togo

Why I am a feminist and I love rap

“Wait, you’re a feminist who likes rap? How does THAT work?” Believe me, I’ve heard that line more times than I can count!

Hip hop and rap have been under fire for their alleged sexism since day one. Fueled by a cocktail of barely-veiled racism, contempt, and sheer ignorance, society relentlessly paints rap as the absolute worst music for women. And yet, here I stand: a white queer, feminist woman with an unshakeable love for rap. Talk about a head-scratcher, right?

Ironically, I discovered feminism through rap, among other things. Back in the mid-1990s, when I was in high school, I was seriously into hip hop dancing and listened to a lot of American female rappers: Queen Latifah, Missy Elliott, Salt N Pepa, MC Lyte, EVE, Lauryn Hill, Da Brat, Lady of Rage, Bahamadia, Rah Digga, Lil’ Kim, Foxy Brown….

I was fascinated by their freedom, their impertinence, and their blunt way of tackling certain topics, such as female sexuality, women’s financial independence, abortion, physical and sexual violence, and, of course, the clitoris, which I discovered thanks to Lil’ Kim’s “Not Tonight”! These were issues I had never even heard of before.

I delved deeper into this subject at university. During my master’s degree, I specialized in African-American feminism and Black Protest movements. I discovered the book When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost by American writer and journalist Joan Morgan, in which she uses the expression “hip hop feminism.” I could totally relate to the term. To me, there was an obvious link between the two.

But very soon, I was told that hip hop and feminism were fundamentally incompatible and that I had to pick a side. If I wanted to be seen as a real feminist, I had to denounce rap. And if I still listened to it alone in my room, like the dirty little secret of some occult allegiance to the patriarchy, I was urged to burn all my records and trash my playlists to replace them with “appropriate” music. The Spice Girls, Taylor Swift or Patti Smith would supposedly do the trick.

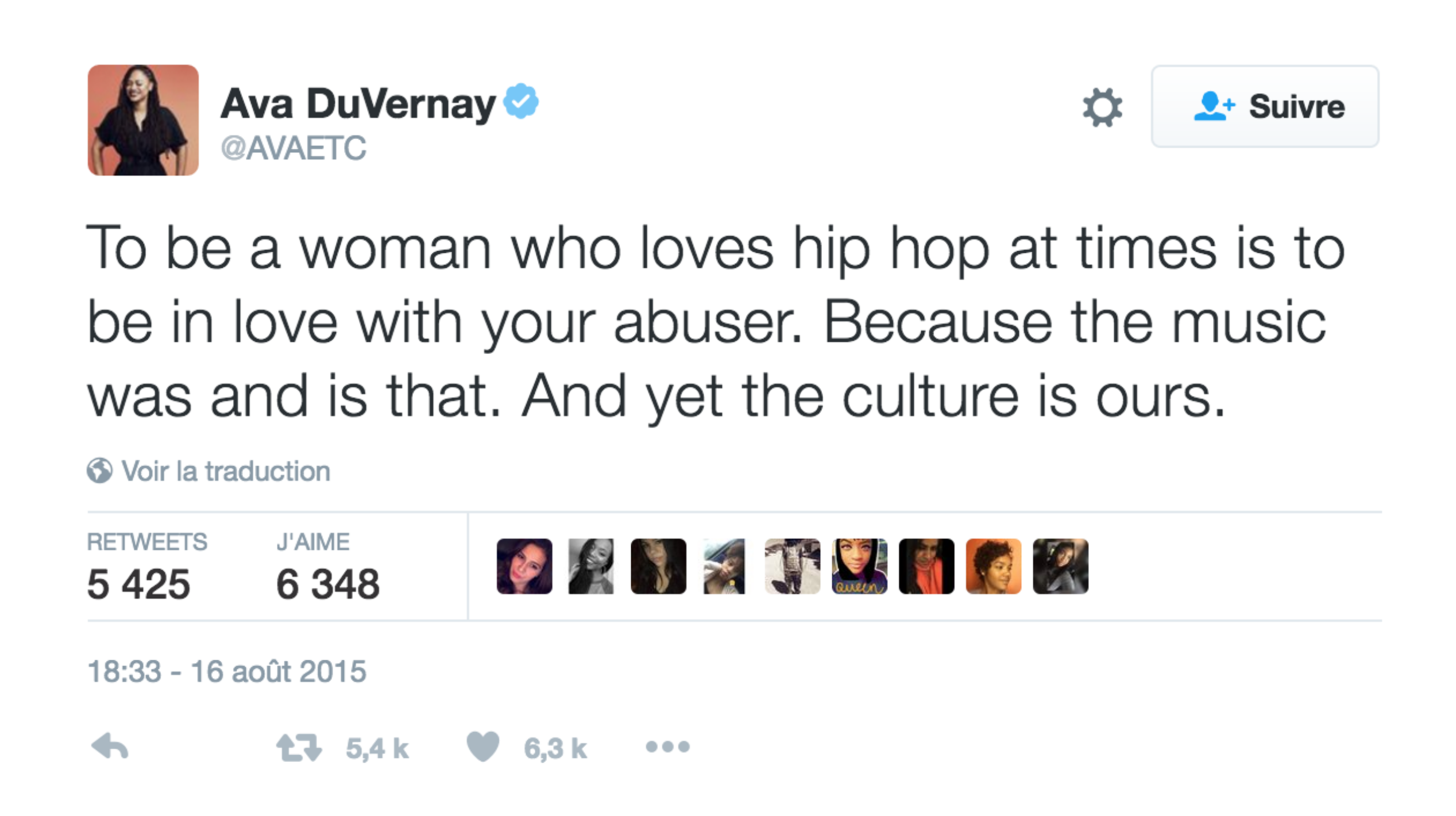

While hip hop lovers never reproached me for being a feminist, others constantly lectured me on how a self-respecting feminist simply couldn’t live with this contradiction. I began to question the source of this conflicted love, which American director Ava DuVernay summarized in one tweet:

“To be a woman who loves hip hop at times is to be in love with your abuser. Because the music was and is that. And yet the culture is ours.“

Could it be denial? Internalized sexism?

And, most of all, why would girls who grew up listening to The Red Hot Chili Peppers, watching Roman Polanski movies, and reading Charles Bukowski somehow be better feminists than me?

Let’s be honest: rap is undeniably a male-dominated, sexist, and LGBTphobic industry. I’m not trying to sugarcoat the situation. A 2009 study shows that between 22% and 37% of rap lyrics are misogynistic, and 67% of rap songs sexually objectify women.

Countless rap lyrics, particularly those from the gangsta rap era, normalize rape culture and glamorize gender-based violence. In the late 1980s and 1990s, NWA contributed to glorifying the caricatural image of hypermasculine “thugs” with big cars, subservient naked women, flowing money, and constant ego-tripping. Dr. Dre‘s infamous line, “If a bitch tries to diss me while I’m full of liquor, I smack the bitch up and shoot the n**** that’s with her,” exemplifies this attitude. However, it’s worth noting that the Compton trio also spoke out against police brutality, systemic racism, violence, and poverty.

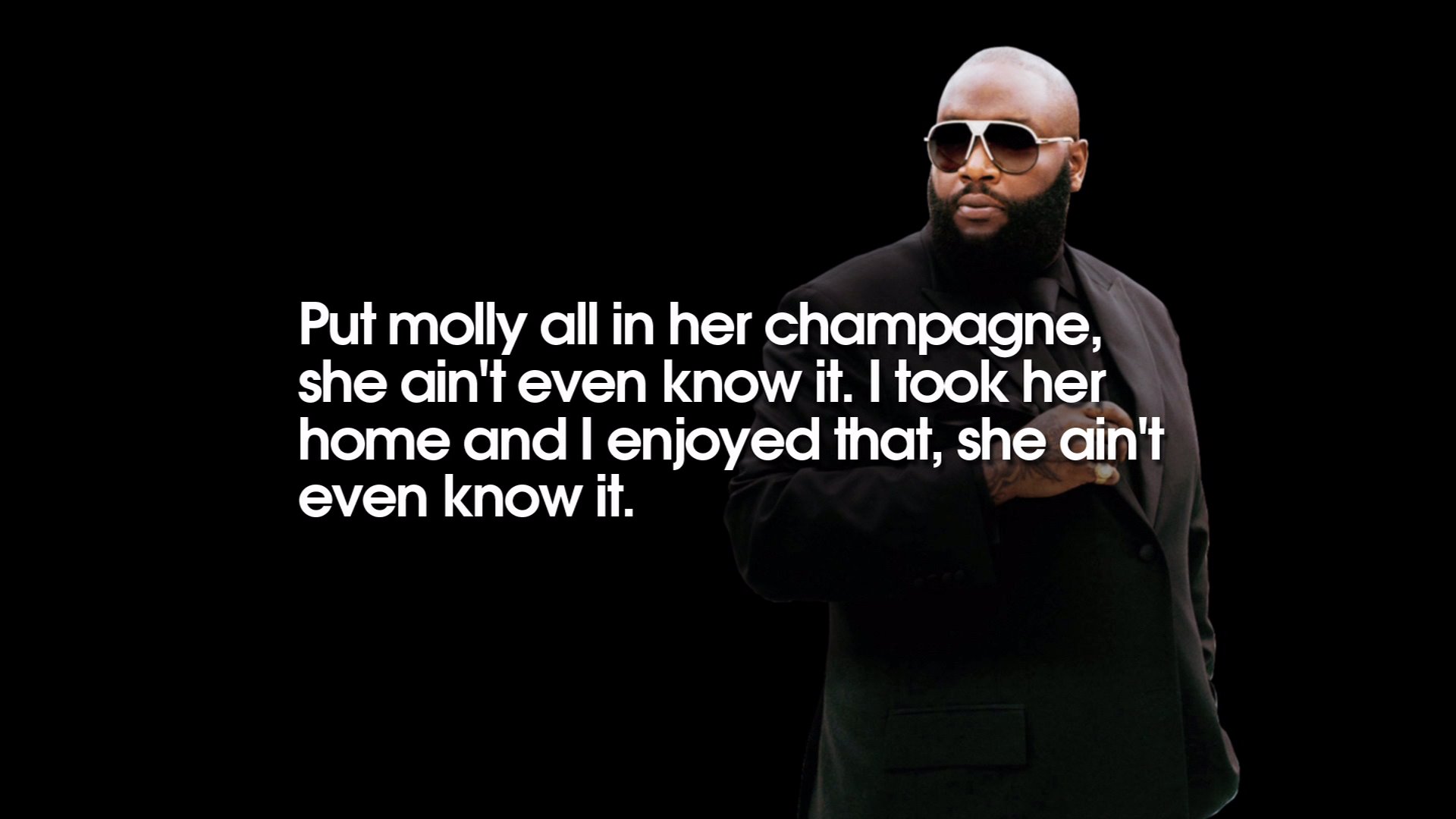

By advocating rape, Rick Ross also incurred feminists’ wrath:“Put molly all in her champagne / She ain’t even know it / I took her home and I enjoyed that / She ain’t even know it” (Rocko ft. Future & Rick Ross – “U.O.E.N.O”).

The problem isn’t limited to American rappers. In France, artists like Booba, Busta Flex, La Fouine, Black M, and Orelsan have all faced criticism for their misogynistic lyrics.

Their words often demean women, glorify sexual assault, and promote harmful stereotypes.

However, it’s crucial to understand that this verbal abuse doesn’t occur in a vacuum. It’s a direct result of how women are treated in our society at large. As writer and activist bell hooks observes, while Black males must be held accountable for their sexism, this critique must always be contextualized:

“Without a doubt Black males, young and old, must be held politically accountable for their sexism. Yet, this critique must always be contextualized or we risk making it appear that the behaviors this thinking supports and condones,–rape, male violence against women, etc.– is a Black male thing. And this is what is happening. Young Black males are forced to take the “heat” for encouraging, via their music, the hatred of and violence against women that is a central core of patriarchy.”

It’s also important to note that not all hip hop is misogynistic. Many male artists, both in the US and France, offer alternative perspectives that break away from common stereotypes of male hegemony. Artists like Shad (from Canada), Talib Kweli, Common, Médine, and Youssoupha present more nuanced and respectful portrayals of women in their music.

Many women in hip hop convey openly feminist and empowering messages.

From pioneers like Queen Latifah, Missy Elliott or Lauryn Hill to contemporary artists like Cardi B, Nicki Minaj, Megan Thee Stallion or Latto to name a few. These women use their platforms to address issues of gender equality, body positivity, and women’s rights.

MC Lyte even called Fetty Wap a feminist for his track “Trap Queen” : “He’s being pretty courageous right now with what it is that he presents in his music, because it’s really not the norm.”

Navigating the complexities of sexism in rap music requires a nuanced approach, as the message isn’t always clear-cut. Take 2Pac, for example. While he offered praise to women in tracks like “Wonda Why They Call U Bitch,” “Keep Ya Head Up,” and “Never Call U Bitch Again,” his conviction for sexually assaulting a woman casts a shadow and makes his music difficult for feminists to reconcile.

Drake faces similar scrutiny. He often portrays himself as a champion of women, yet he raps in “Paris Morton Music”: “I hate calling the women bitches but the bitches love it,” creating a jarring disconnect.

However, it’s crucial to recognize that rap is not uniquely sexist compared to other musical genres. Its use of direct and explicit language simply brings the issue to the forefront, making it more visible.

Other genres often employ more subtle, mainstream, and arguably more insidious forms of sexism that go largely unchallenged.

A deeper look into popular music reveals that misogyny isn’t confined to rap.

- Nick Cave and Johnny Cash‘s “Murder Ballads” delve into the grim territory of femicide.

- Pink Floyd sings of the desire to “beat to a pulp on a Saturday night“(“Don’t Leave Me Now”).

- Tom Jones confesses, “I felt the knife in my hand and she laughed no more“(“Delilah”).

- Even The Misfits threaten, “If you don’t shut your mouth you’re gonna feel the floor” (“Attitude”).

- John Lennon, despite his advocacy for peace and love, also contributed to this problematic narrative with lyrics like, “I’d rather see you dead, little girl than to be with another man” (“Run For Your Life”).

- The Rolling Stones further complicate the picture, singing, “under my thumb she’s the sweetest pet in the world / It’s down to me the way she talks when she’s spoken to“, (“Under My Thumb”) painting a picture of female subjugation.

These examples demonstrate that problematic portrayals of women are widespread across musical genres, demanding a broader conversation about sexism in music as a whole.

This isn’t solely an issue within the American music landscape. In France, equally troubling examples of misogyny and violence against women can be found in the work of popular and influential artists such as Michel Delpech, Georges Brassens, Julien Clerc, and Michel Sardou.

The question then arises: why are we more offended by rap lyrics than these other similarly problematic instances? A likely explanation lies in the fact that hip hop has historically been marginalized and examined through a lens of racism and classism.

When white, “respectable” men promote what’s perceived as an acceptable form of masculinity in their music, they’re often held up as cultural icons. We applaud these popular artists for expressing their sexual desires, even when those desires objectify women and disregard the question of consent, precisely because it’s packaged within the guise of romanticism and love songs.

As a consequence, we internalize these damaging stereotypes. We’re conditioned to see these mainstream singers as gentlemen, while dismissing male rappers as narrow-minded, misogynistic, capitalist or uneducated delinquents.

This ingrained bias prevents us from critically examining sexism across all musical genres and perpetuates harmful prejudices against hip hop culture.

As a feminist and activist, I’m unapologetically drawn to the raw energy, the unflinching language, and the powerful narratives of artists like Nicki Minaj, Cardi B, Glorilla or Young MA. Their music resonates with me in a way that the sanitized sounds of Ed Sheeran or Maroon 5 simply never could. This isn’t just a preference; it’s a source of empowerment.

To me, feminism means making conscious choices: choosing my battles, choosing the voices I amplify, and owning my own contradictions.

Within hip hop, I find a vibrant ecosystem of diverse female representation that’s painfully absent elsewhere. Where else can I see women of all backgrounds – representing a kaleidoscope of origins, ages, classes, religions, sexual orientations, gender identities, and body types – speaking frankly and fearlessly about everything from their own sexual pleasure and body positivity to the harsh realities of domestic violence, systemic inequalities, the urgent issues of politics and police brutality, and the pervasive forces of racism, sexism, LBTphobia, and even the intricate ethical considerations surrounding Assisted Reproductive Technology?

Certainly not in the often-homogenous worlds of rock, pop, or French chanson. In France, especially, rap stands as a uniquely vital space, offering a platform where women can freely tell their stories, unfiltered. That’s why I’m a feminist. That’s why I’ll always love rap. It’s not just music; it’s a revolution in sound.

A short version of this article was published in French in Le Huffington Post: here.

Ms Banks

NAME: Ms Banks

TRACK: The Get Back

YEAR: 2015

FROM: London, UK

D’ de Kabal: “Many male rappers think they’re revolutionaries but never talk about sexism or homophobia”

When and how did you start to rap?

I started to rap at the age of 19 after an Assassin concert. It was in 1993, during their “Le futur que nous réserve-t-il ?” tour. I went to see them with my homie Djamal and we were blown away. It was Rockin’ Squat, Solo, Doctor L on drums and Dee Nasty on the decks. We thought we had to make a rap band. So we launched Kabal. We met Assassin and we really hit it off.

The next tour, we were on stage with them and they produced one of our EPs in 1996. We spent two great years by their side, which allowed us to spread nationally at a time when Internet didn’t exist. Otherwise, I liked writing essays in school so rap was a way for me to pursue my love for writing and put it into words.

Which artists did you listen to?

At the time, I listened to everything. NTM first albums, Timide & Sans Complexe, Ministère A.M.E.R., Les Little … We bought all new French rap music. As far as I can remember, I had my first thrills with Eric B & Rakim, LL Cool J, all these guys.

And women?

Very few. At the time, it was MC Lyte, Queen Latifah, Yo-Yo, and later Foxy Brown, Lil’ Kim, Missy Elliott. In France, I loved Saliha’s first single. Melaaz too, we were really proud when she was invited on Kabal’s album. Later, Princess Anies and Sté Strausz. I met Nina Miskina, who was a big crush. A real hardcore and angry girl. Casey, she’s kind of my writing sister, we know each other well and respect each other.

Your music evolved quickly and your worked on very diversified projects…

I quickly met jazz musicians. I had only been rapping for four or five years and I found myself playing with avec Marc Ducret, Hélène Labarrière or Benoît Delbecq, big names of the French jazz improv scene. I thought I had to be skillful with words, as they were with their instrument.

When Djamal and I worked on Kabal debut album, we decided to perform with live musicians. We formed this incredible team with DJ Toty, rock guitar player Skalp, afro bass player Professor K, and jazz drummer Franck Vaillant. We started to jam regularly and it opened my spectrum of possibilities.

When we toured with Assassin between 1995 and 1997, we met a lot of people and had to face their judgement. After this tour, I realized I didn’t want to be taken for a kind of ruthless warrior, who eats organic, doesn’t put his money in the bank, doesn’t buy Nike sneakers and doesn’t drink Coke. I wanted to find another truth and show I was more complex than that.

All that conditioned my work on my first solo album. I tried to confuse the listeners with humoristic, weird or loony tracks, that allowed me to go where I wanted to. Then, I worked on other projects, like La théorie du K.O. and Spoke Orkestra, that made me evolve. I always wanted to do a lot of things at the same time.

How did you start working in theater?

It happened by accident. In 1998, I met the author Mohamed Rouabhi, who made me act in a few plays. At the beginning, I was doing bit parts or musical parts. His texts were sick, it was really committed theater, even if the word “committed” is timeworn today.

I was then directed by Stéphanie Loïk and I performed with Hassane Kouyaté, who asked me one day if I had ever written theater plays. I took it like a challenge and thought it was like writing a rap song, but only longer. I wrote my first play and it was the trigger. I never stopped writing ever since. I founded my own troupe R.I.P.O.S.T.E. in 2005 and realized there was an empty space in French theater that I wanted to fill.

Today, I’m a writer, director and actor. I like to work in collaboration with other people, especially when it comes to stage directing. My shows are usually musical and I love the idea of working to transform materials.

When and how did you begin to develop a “feminist consciousness”?

I always wrote tracks about these issues. Some people are antisexist but racist, others are antiracist but homophobic… It has always bothered me. My reflection on women came from there. Besides, as a man, I thought it was the most complex topic to tackle.

Once, my mother made homophobic remarks in my home and I hauled her over the coals. For me, that’s what being committed means. Having a committed approach is a business but being committed in your everyday life with your nearest and dearest is different. Regularly, I do what I call updates, and sort out my relations. It causes frictions.

That’s what “Punchlines” is about: it’s not very brave to call yourself a “committed writer” and not to talk about vexing questions. By vexing questions, I mean questions that vex our entourage. Many male rappers think they’re revolutionaries and acerbic writers but never talk about sexism or homophobia. It is whether because there isn’t any around them, which would be surprising, or that they choose not to talk about it. In that case, it is a problem to me.

Do you consider yourself a feminist? If so, how is it perceived?

I consider myself a feminist or a pro-feminist, both are OK to me. I have feminist female friends who tell me that I can’t call myself a feminist because I am a man. But because I am a man of words, when I’m told that I can’t say something, it goes in one ear and out the other! It’s like when people tell me I don’t do rap, I don’t mind and I understand. Because my music is very special. I am a humanist, because it includes everything.

Rap is often perceived as one of the sexiest musical genres. What do you think about that?

There is sexism in rap and I fight against it, but rap isn’t more sexist than society. If people fought against sexism in politics, advertising and everywhere before criticizing hip hop, I wouldn’t wind. I know people who are on all fronts all year long and I accept their critics. They don’t put any struggle above the other. On the other hand, I can’t accept hypocritical people who say rap is the sexiest music in the world. Rap should then be cleaner than the world it comes from?! It’s a way to stigmatize working classes once again, whereas the rest of society is misogynous. I think it’s complete bullshit.

How do men react to your work?

I had crazy feedbacks on my play L’homme-femme, les mécanismes invisibles, that I created in 2015. An octogenarian who saw the show in Avignon told me this beautiful thing: ”It’s an unknown speech that I recognized”. This kind of touching feedback encouraged me to keep exploring the subject.

What are your upcoming projects?

I just released the 7-track mixtape FB (Faces B) Saturation. This project started because I wanted to spit on American instrumentals. The mixtape compiles Facebook posts that I never published or rewrote. It was fun to give a musical life to public writings and to work on this transformation. I think I will do this regularly because it feels food to go back in the studio, even if I don’t feel like making a rap album again.

I also have my project Trioskyzophony,an improvisation vocal hip hop band launched four years ago. It is a flexible collective with three different versions and we organize Microphone Clubs, where we play live and have guests.

In June, I put on my three-part theater play Fêlures (Cracks) about the feminine and the masculine.

I also launched the Laboratoires de déconstruction et revalorisation du masculin par l’art et le sensible (Laboratories of deconstruction and revaluation of the masculine through arts and senses), a task force that will identify, question and fight sexisms and the mechanisms of male domination. We will meet twice a month in Bobigny and Villetaneuse for free 2 or 3 hour sessions. Men who want to join can contact me on my Facebook page.

The project was born when I realized society put men in a place without any reflection or discussion, like a sheep-like reflex. It freaked me out. When I talked about it in my inner circle, I realized there was an area of reflection that nobody wanted to explore. I thought it was interesting and I began to work on myself.

I am a West Indian, a descendant of slaves and I live in France. I can talk about racism as a potential victim. I wondered what it would be like for me to put myself in the persecutor’s place on some issues. I immediately thought about violence against women and looked deeper into it. It was fascinating to think about which speech I wanted to build and which thoughts I wanted to bring. My work method is really about thinking, put these thoughts into words and pass them over.

What do you think about Madame Rap? What should be changed or improved?

Maybe it would be interesting to have live videos of female rappers. I think the concept is sick. Since I want to give women more visibility, especially in my Microphone Clubs, it is a goldmine and I’m very happy!

Find D’ de Kabal on YouTube.

© Photo : Alma

Bad Gyal

NAME: Bad Gyal

TRACK: Mercadona

YEAR: 2016

FROM: Spain

Sosuun

NAME: Sosuun

TRACK: KUFUNIKWA

YEAR: 2016

FROM: Kenya

Barf Troop

NAME: Barf Troop

TRACK: Martians

YEAR: 2015

FROM: USA

La Blondie

NAME: La Blondie

TRACK: Trap

YEAR: 2016

FROM: Barcelona, Spain