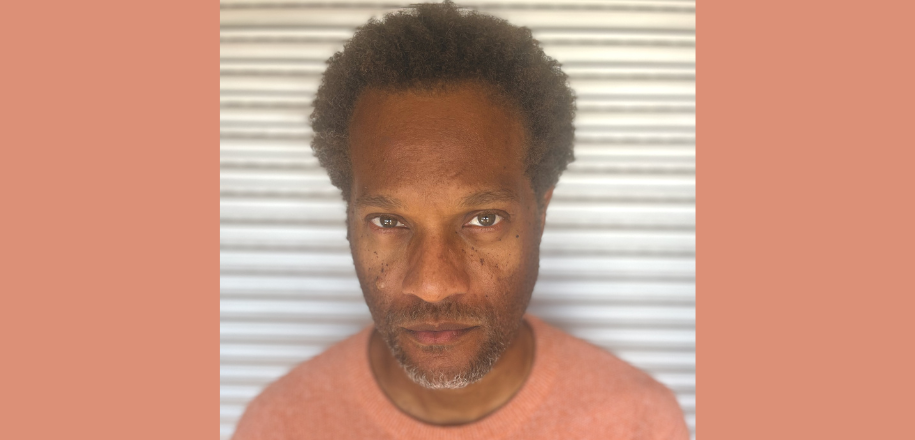

A reference on the Mexican feminist music scene, Masta Quba defines herself as an “MC and educator”. Active for 18 years, she uses rap as a tool of resistance and transmission to denounce gender violence and systemic racism. Currently based in Barcelona, the rapper told to us about her creative process, the importance of creating community and the perception of female rappers in Mexico.

How and when did you discover hip hop?

I discovered hip hop thanks to MTV when I was 14. I’ll never forget how I felt when I discovered rap. The first song I heard was “El Juego Verdadero” by Tiro de Gracia, a Chilean rap group. For me, it was a feeling I couldn’t explain. More than anything, I think hip hop discovered me. And from that moment on, I never stopped listening to it.

I started buying bootlegs in the street markets in my neighborhood and downloading music when there was no YouTube or any of that stuff. That’s how hip hop got to me. I’ve never let it go since I was 14, and now I’m 36.

Are you self-taught or did you receive any musical education?

I’ve had no musical training whatsoever. In fact, everything comes from my experience and my musical ear. I’d like to take singing lessons, piano lessons or at some point learn to produce, buy a machine and all the rest. But life has caught up with me and I haven’t yet managed to have the means to buy or invest in more formal musical training.

I think that’s the beauty of rap: anyone can do it. All you need is a pen, a piece of paper and a story to tell. It’s good that at some point you start to educate yourself musically, that you evolve and can train more.

But you also have to understand that conventional musical training is not accessible to everyone.

Being able to afford an academy or school depends a lot on who you are and your social class. As for me, I make music in an informal way. It’s the years that have sharpened me.

You started rapping in 2007 in mostly male freestyles. What prompted you to take part in these events and how were you received?

I started rapping more officially in 2007. It was the first time I went to a reggae/rap event where Alika and Nueva Alianza were performing. People were partying, enjoying the evening, and I saw a circle of men doing a freestyle. I recognized the four beats, the boom bap and the hip hop vibe. I went to cheer them on.

From then on, I became friends with these people, most of whom were men. In the end, for a lot of women who started out in the 2000s or 1990s,

our only option for being part of the culture was to be with men.

I was pretty well welcomed.

Later, when I started to develop a political base, these same men made fun of me for taking feminist or anti-racist positions, for stopping freestyling and starting to make songs with more political and introspective content…

You define yourself as a rapper and hip hop activist. In your opinion, what’s the difference between the two?

I define myself as an MC and a hip hop activist because I think activism is something that has to stay alive. I can be an MC at an event and give everything on stage. But for me, activism also means being present everywhere.

I’m an educator, giving hip hop workshops for women, girls, children or mixed with a gender, class and race perspective.

For this reason, I define myself as an activist. That’s what makes it possible to move from theory to action. For me, it’s not enough to say I do hip hop or rap if I can’t do a thousand other things that have to do with the culture as well.

Because at the end of the day, hip hop isn’t just about rap. For me, rapping is one thing, but breathing, living and doing hip hop every day is another. Because it’s in your daily life, in your actions, in the way you help others and mingle with your community.

What is your definition of feminist hip hop?

About seven years ago, I had a very clear-cut approach and liked to say I was doing feminist rap. Over the years, and with the political grounding I’ve acquired, the people around me have made my discourse evolve a little in line with my lifestyle.

Rather than calling the rap I do feminist, I prefer to call it simply hip hop.

Because basically, if it’s not feminist, anti-racist, anti-colonial or political, for me it’s not hip hop.

It’s up to me. So I think any woman today can start rapping in honor of all the women who have rapped since it all started. Because we’ve never been in the minority, and there’s never been a hip hop without us. And the day we leave, there’ll be no more hip hop.

But I think feminist hip hop goes hand in hand with anti-racist hip hop and anti-colonial, anti-capitalist hip hop.

Which feminist movement do you feel closest to?

If I had to choose one feminist trend, it would be anti-colonial, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist and anti-colonialist black feminism.

You use hip hop as an artistic tool in your workshops and conferences. What kind of audience do these events target, and how do the participants respond?

Yes, I use hip hop as a tool for workshops and conferences. Personally, I’d use them for anyone. But obviously, not everyone is in the same situation or at the same political level. That’s not to say it’s bad or good, but I’ve now learned that I resonate with whoever resonates with me.

The way we think or the currents we identify with are never isolated.

You’ll always find a colleague you can relate to.

The workshops are aimed at a lot of high schools, because we really enjoy working with teenagers. We think that’s where we can sow the seeds to provide them with more tools. Especially in today’s world, which is so technological and disconnected from introspection and the creation of one’s own identity.

The workshops are aimed at young people, women and anyone who wants to tell their story and resonate with a political discourse where all worlds are in agreement. And where all people have rights.

From a musical point of view, how would you describe your music?

I would say that my music lives, tells, makes uncomfortable, questions, accompanies, evolves, grows, develops, changes and transforms.

I also think I’ve made a lot of progress. In terms of my rap, my technique, my productions and the quality of my project. All in all, I think that beyond the lyrics, my project is also very interesting.

How do you usually write your lyrics? What’s your creative process?

Instead of sitting down to see what I’m writing, I sit down because I have to write. Practically all my music comes from my life story, from what’s going through me or the world. In reality, I always take a very political look at what’s destroying us, but also a lot of comfort and introspection, which remains political because the personal is political.

My process consists of opening wounds, cleaning them, treating them, healing them, and that’s how the stories I tell come out.

I also need to have a ritual: hanging a candle, incense, being alone, it also has to happen at night.

And from a technical point of view, I start by playing with the beat, humming, testing flows, then I add lyrics.

But to write, I need to have lived an experience in order to recount it. I’ve never written something fictional that I thought was beautiful. My process comes from a story, from telling myself.

Which track(s) are you most proud of so far, and why?

Almost all of them. Some are still more important, given their history and impact. For example, “Nosotras tenemos otros datos”, where I talk about the increase in the number of feminicides in Mexico linked to the pandemic:

11 women are murdered in Mexico every day.

There’s also a song about abortion where I tell the story of how I accompanied myself when I had an abortion in 2017. I’ve accompanied a lot of girls and buddies who have gone through these same ordeals because women have abortions. And the fight goes on to make people understand that it’s a human right.

“Despiertas” is another song I really like, because the musical production was very heavy. We were in a very big studio and it was mixed in Dolby Atmos, which was a first for me.

“Autodefensa” and “Rebobina” are also important songs for me.

In fact, I cherish each track and remind myself that I should be proud of it.

I remind myself that it’s important for us women to recognize our true worth.

Because this society sometimes lets us think that recognizing our true worth is arrogance or something like that.

How does the Mexican audience respond to female rappers?

In Mexico, the level of machismo and misogyny is very high.

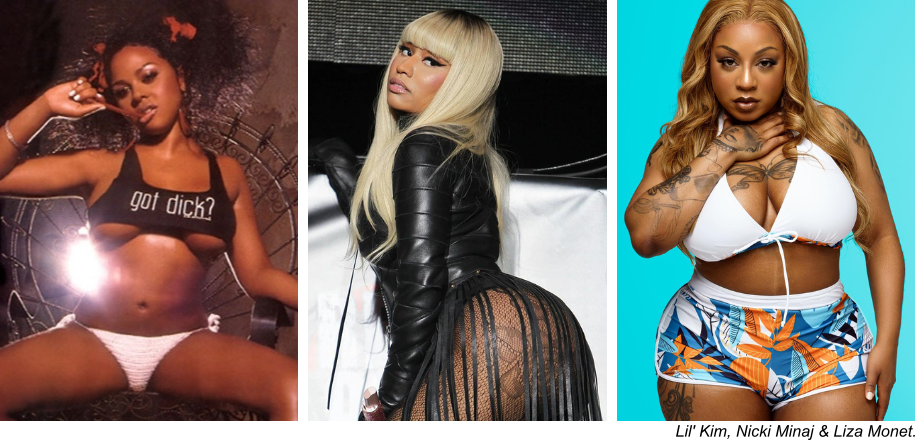

To be recognized as a female rapper, you have to fit the stereotype that rappers have created.

In other words, Mexican rappers have a cliché in their heads of what a female rapper should look like, and if you don’t fit that stereotype, they reject you.

You have to obey certain standards of beauty and certain themes. If you’re a feminist rapper, you get all the hate and mockery, because Mexico is still very backward on these issues.

If you’re a non-feminist rapper but you choose to show your body, because you have every right to and because it’s natural, they see you as the rapper they want to fuck and that’s the end of it for you.

For them, there are rappers they want to fuck and rappers they don’t want to fuck. That’s how I’d sum it up. I see it with my fellow female rappers. Sometimes the ones who are respected are the girlfriends of another respected rapper.

You’ve been involved in several tracks with Mexican or Spanish-speaking female rappers. Why is it important for you to collaborate with other female rappers?

Last year, I did a lot of collaborations. For me, it’s all about networking. The music industry always chooses who they put at the “top”. The idea of success was created by the industry to never be reached. A rap that’s political, male, female or dissident has little chance of being truly popular.

The only way for us to grow is to watch each other. And that’s what I do. I don’t mind working. As far as I’m concerned, I don’t look at the numbers because they’re just numbers. I look at people’s energy, if it’s flowing and if we understand each other, if we have things in common, if there’s mutual admiration….

And for me, that’s important because I think it’s the only way to build a network.

To support each other as women, there’s no other way than to create a community.

As an artist, what are the main obstacles you’ve encountered or are encountering?

I think it’s always been the music industry. Tomorrow, if they delete all my Spotify and YouTube profiles, I’ll still be making music. Because it’s something I’ve done all my life and I can’t see myself doing anything else.

It’s my food for continuing to exist in a world as dreadful as the one we live in now.

What are your upcoming projects?

Among my upcoming projects is my album. I’m going to start by sharing two or three tracks with featurings, which I’ve had on hold for the past year. Then, if all goes well and the stars align, I’ll be able to release it this year. There are some really great things to come on this album.

This is my first solo album. I released my first album in 2022 with P. Jaguar, who is my partner, and I did it with him, both 50/50 in terms of rapping and everything else. P. Jaguar is back again on this album, producing all the tracks.

There are also a few concerts and a tour coming up. If all goes well, some of my tracks will be in two Netflix series coming out this year. I’m lighting a candle to make it all happen!

Find Masta Quba on Instagram, TikTok, X, YouTube and Facebook.