“Wait, you’re a feminist who likes rap? How does THAT work?” Believe me, I’ve heard that line more times than I can count!

Hip hop and rap have been under fire for their alleged sexism since day one. Fueled by a cocktail of barely-veiled racism, contempt, and sheer ignorance, society relentlessly paints rap as the absolute worst music for women. And yet, here I stand: a white queer, feminist woman with an unshakeable love for rap. Talk about a head-scratcher, right?

Ironically, I discovered feminism through rap, among other things. Back in the mid-1990s, when I was in high school, I was seriously into hip hop dancing and listened to a lot of American female rappers: Queen Latifah, Missy Elliott, Salt N Pepa, MC Lyte, EVE, Lauryn Hill, Da Brat, Lady of Rage, Bahamadia, Rah Digga, Lil’ Kim, Foxy Brown….

I was fascinated by their freedom, their impertinence, and their blunt way of tackling certain topics, such as female sexuality, women’s financial independence, abortion, physical and sexual violence, and, of course, the clitoris, which I discovered thanks to Lil’ Kim’s “Not Tonight”! These were issues I had never even heard of before.

I delved deeper into this subject at university. During my master’s degree, I specialized in African-American feminism and Black Protest movements. I discovered the book When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost by American writer and journalist Joan Morgan, in which she uses the expression “hip hop feminism.” I could totally relate to the term. To me, there was an obvious link between the two.

But very soon, I was told that hip hop and feminism were fundamentally incompatible and that I had to pick a side. If I wanted to be seen as a real feminist, I had to denounce rap. And if I still listened to it alone in my room, like the dirty little secret of some occult allegiance to the patriarchy, I was urged to burn all my records and trash my playlists to replace them with “appropriate” music. The Spice Girls, Taylor Swift or Patti Smith would supposedly do the trick.

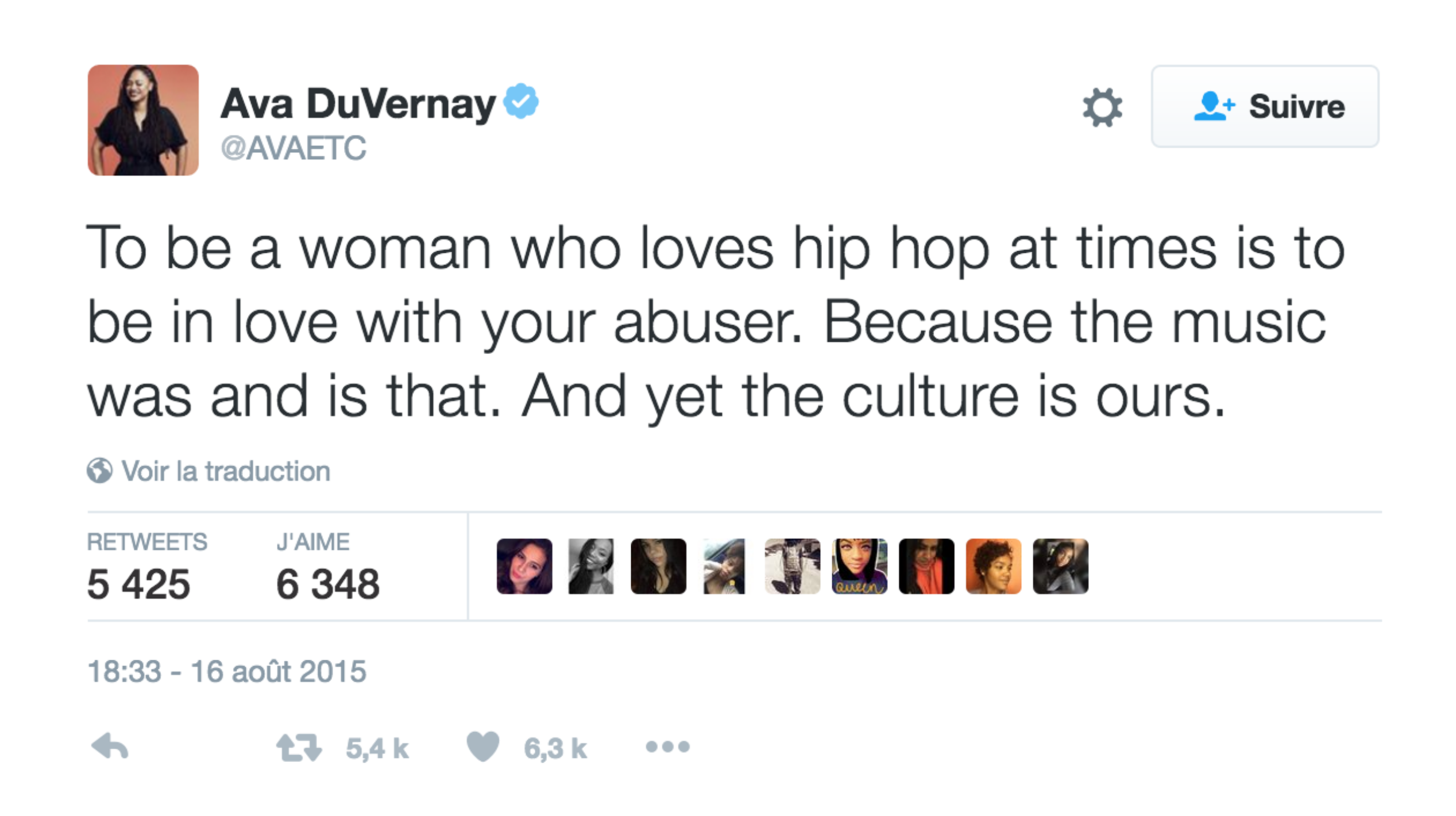

While hip hop lovers never reproached me for being a feminist, others constantly lectured me on how a self-respecting feminist simply couldn’t live with this contradiction. I began to question the source of this conflicted love, which American director Ava DuVernay summarized in one tweet:

“To be a woman who loves hip hop at times is to be in love with your abuser. Because the music was and is that. And yet the culture is ours.“

Could it be denial? Internalized sexism?

And, most of all, why would girls who grew up listening to The Red Hot Chili Peppers, watching Roman Polanski movies, and reading Charles Bukowski somehow be better feminists than me?

Let’s be honest: rap is undeniably a male-dominated, sexist, and LGBTphobic industry. I’m not trying to sugarcoat the situation. A 2009 study shows that between 22% and 37% of rap lyrics are misogynistic, and 67% of rap songs sexually objectify women.

Countless rap lyrics, particularly those from the gangsta rap era, normalize rape culture and glamorize gender-based violence. In the late 1980s and 1990s, NWA contributed to glorifying the caricatural image of hypermasculine “thugs” with big cars, subservient naked women, flowing money, and constant ego-tripping. Dr. Dre‘s infamous line, “If a bitch tries to diss me while I’m full of liquor, I smack the bitch up and shoot the n**** that’s with her,” exemplifies this attitude. However, it’s worth noting that the Compton trio also spoke out against police brutality, systemic racism, violence, and poverty.

By advocating rape, Rick Ross also incurred feminists’ wrath:“Put molly all in her champagne / She ain’t even know it / I took her home and I enjoyed that / She ain’t even know it” (Rocko ft. Future & Rick Ross – “U.O.E.N.O”).

The problem isn’t limited to American rappers. In France, artists like Booba, Busta Flex, La Fouine, Black M, and Orelsan have all faced criticism for their misogynistic lyrics.

Their words often demean women, glorify sexual assault, and promote harmful stereotypes.

However, it’s crucial to understand that this verbal abuse doesn’t occur in a vacuum. It’s a direct result of how women are treated in our society at large. As writer and activist bell hooks observes, while Black males must be held accountable for their sexism, this critique must always be contextualized:

“Without a doubt Black males, young and old, must be held politically accountable for their sexism. Yet, this critique must always be contextualized or we risk making it appear that the behaviors this thinking supports and condones,–rape, male violence against women, etc.– is a Black male thing. And this is what is happening. Young Black males are forced to take the “heat” for encouraging, via their music, the hatred of and violence against women that is a central core of patriarchy.”

It’s also important to note that not all hip hop is misogynistic. Many male artists, both in the US and France, offer alternative perspectives that break away from common stereotypes of male hegemony. Artists like Shad (from Canada), Talib Kweli, Common, Médine, and Youssoupha present more nuanced and respectful portrayals of women in their music.

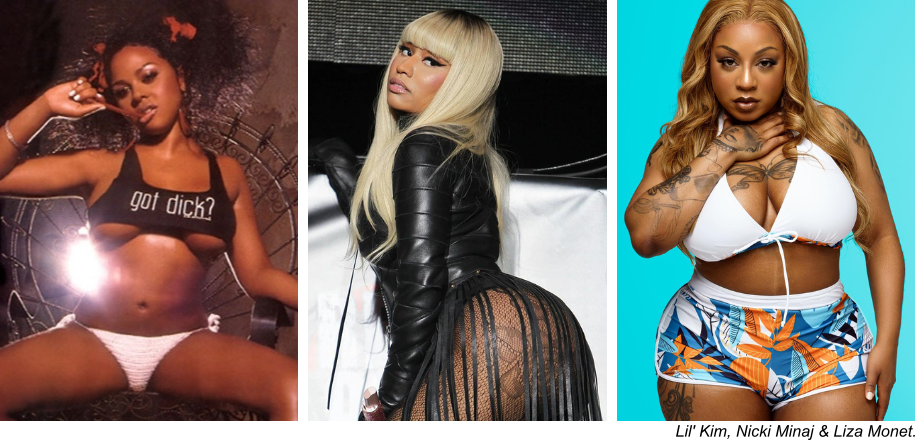

Many women in hip hop convey openly feminist and empowering messages.

From pioneers like Queen Latifah, Missy Elliott or Lauryn Hill to contemporary artists like Cardi B, Nicki Minaj, Megan Thee Stallion or Latto to name a few. These women use their platforms to address issues of gender equality, body positivity, and women’s rights.

MC Lyte even called Fetty Wap a feminist for his track “Trap Queen” : “He’s being pretty courageous right now with what it is that he presents in his music, because it’s really not the norm.”

Navigating the complexities of sexism in rap music requires a nuanced approach, as the message isn’t always clear-cut. Take 2Pac, for example. While he offered praise to women in tracks like “Wonda Why They Call U Bitch,” “Keep Ya Head Up,” and “Never Call U Bitch Again,” his conviction for sexually assaulting a woman casts a shadow and makes his music difficult for feminists to reconcile.

Drake faces similar scrutiny. He often portrays himself as a champion of women, yet he raps in “Paris Morton Music”: “I hate calling the women bitches but the bitches love it,” creating a jarring disconnect.

However, it’s crucial to recognize that rap is not uniquely sexist compared to other musical genres. Its use of direct and explicit language simply brings the issue to the forefront, making it more visible.

Other genres often employ more subtle, mainstream, and arguably more insidious forms of sexism that go largely unchallenged.

A deeper look into popular music reveals that misogyny isn’t confined to rap.

- Nick Cave and Johnny Cash‘s “Murder Ballads” delve into the grim territory of femicide.

- Pink Floyd sings of the desire to “beat to a pulp on a Saturday night“(“Don’t Leave Me Now”).

- Tom Jones confesses, “I felt the knife in my hand and she laughed no more“(“Delilah”).

- Even The Misfits threaten, “If you don’t shut your mouth you’re gonna feel the floor” (“Attitude”).

- John Lennon, despite his advocacy for peace and love, also contributed to this problematic narrative with lyrics like, “I’d rather see you dead, little girl than to be with another man” (“Run For Your Life”).

- The Rolling Stones further complicate the picture, singing, “under my thumb she’s the sweetest pet in the world / It’s down to me the way she talks when she’s spoken to“, (“Under My Thumb”) painting a picture of female subjugation.

These examples demonstrate that problematic portrayals of women are widespread across musical genres, demanding a broader conversation about sexism in music as a whole.

This isn’t solely an issue within the American music landscape. In France, equally troubling examples of misogyny and violence against women can be found in the work of popular and influential artists such as Michel Delpech, Georges Brassens, Julien Clerc, and Michel Sardou.

The question then arises: why are we more offended by rap lyrics than these other similarly problematic instances? A likely explanation lies in the fact that hip hop has historically been marginalized and examined through a lens of racism and classism.

When white, “respectable” men promote what’s perceived as an acceptable form of masculinity in their music, they’re often held up as cultural icons. We applaud these popular artists for expressing their sexual desires, even when those desires objectify women and disregard the question of consent, precisely because it’s packaged within the guise of romanticism and love songs.

As a consequence, we internalize these damaging stereotypes. We’re conditioned to see these mainstream singers as gentlemen, while dismissing male rappers as narrow-minded, misogynistic, capitalist or uneducated delinquents.

This ingrained bias prevents us from critically examining sexism across all musical genres and perpetuates harmful prejudices against hip hop culture.

As a feminist and activist, I’m unapologetically drawn to the raw energy, the unflinching language, and the powerful narratives of artists like Nicki Minaj, Cardi B, Glorilla or Young MA. Their music resonates with me in a way that the sanitized sounds of Ed Sheeran or Maroon 5 simply never could. This isn’t just a preference; it’s a source of empowerment.

To me, feminism means making conscious choices: choosing my battles, choosing the voices I amplify, and owning my own contradictions.

Within hip hop, I find a vibrant ecosystem of diverse female representation that’s painfully absent elsewhere. Where else can I see women of all backgrounds – representing a kaleidoscope of origins, ages, classes, religions, sexual orientations, gender identities, and body types – speaking frankly and fearlessly about everything from their own sexual pleasure and body positivity to the harsh realities of domestic violence, systemic inequalities, the urgent issues of politics and police brutality, and the pervasive forces of racism, sexism, LBTphobia, and even the intricate ethical considerations surrounding Assisted Reproductive Technology?

Certainly not in the often-homogenous worlds of rock, pop, or French chanson. In France, especially, rap stands as a uniquely vital space, offering a platform where women can freely tell their stories, unfiltered. That’s why I’m a feminist. That’s why I’ll always love rap. It’s not just music; it’s a revolution in sound.

A short version of this article was published in French in Le Huffington Post: here.