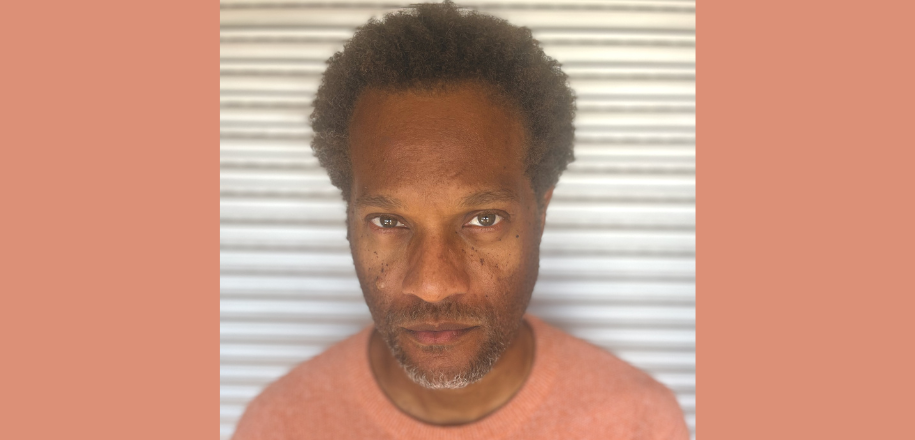

Born in La Paz, Bolivia, Hyena is a rapper, beatmaker and producer. She told us about her career, her involvement in the Brussels-based queer collective Gender Panik, the place of female rappers on the Bolivian scene, and the evolution of her music, which is closely linked to her transidentity.

Hyena has changed her stage name since this interview was published and is now known as Kiya.

Can you briefly introduce yourself?

I go by Hyena on stage and in my job, but everyone knows me by my real name, Nayra. I’m a Bolivian trans girl from the cities of La Paz and Cochabamba. I come from an urban Quechua “mestizo” family, and grew up between the narrow streets and the “motes de habas” that my mother ate every day.

I consider myself a full-fledged trans woman (in European terms), but I identify more with the informal, reappropriated words of my urban culture: minita, imilla, ñoja, chotita, bandida, arrecha, birlocha, desputera, ñata, zorra…

When and how did you discover hip hop culture?

I’ve always been a music and dance fan. As a teenager, I loved watching battles and listening to American and Latin rappers. But my real contact with the culture began in 2021, when I moved back to Bolivia.

I came with the desire to rap, to immerse myself completely in the scene. I started going to rap events and discovering the artists active at the time, and then my big brother and teacher Alandino organized a free rap workshop. It was in this workshop that my first crew Rimay Tinku was born, with whom I did my first scenes and met a lot of people in the culture. And that’s where I stayed.

Did you receive any musical training or education?

I had a guitar teacher for a while, when I was 13 or 14. After that, I just watched videos on YouTube. I learned a lot on my own, by reading and being curious.

When and how did you start rapping?

I started rapping around 2018-2019. At the time, I had a friend who was already rapping, and seeing him write motivated me to get started, even though I wasn’t showing anyone anything, and even though I was doing or wanted to do another kind of music.

I also spent a lot of time alone. At the time, I was living in Brussels in a basement with no doors or windows, locked in my world, composing songs, looking for a purpose. Things got out of hand and I ended up living in a squat with a lot of people.

Among them were my friends who were to become the rap group Gender Panik. Seeing them organize residencies without cis men, where they were allowed to rap and read texts, seeing them motivated and not afraid of not being an “artist”, made me believe more in my rap. And then one thing led to another.

How did you choose your stage name and create your character? How would you define it?

Between May and July 2023, I was constantly dreaming of hyenas. And I never saw any! But I did dream that there was a scavenging animal inside me, hyperactive, eager to get out and show its teeth.

Shortly afterwards, I heard a very powerful story about my birth, my mother, my father, my mother’s pregnancy and a twin I had who unfortunately didn’t live. That apparently I had eaten him in the womb, that apparently I was expected to be born a girl, but turned out to be a boy…. And I went on dreaming, thinking about hyenas.

Watching documentaries, I discovered that female hyenas were a bit like hermaphrodites, and that many biologists confused them with males. The name made more sense, something was asking me to give this name to my work and my expression. And the truth is, it sounds better, it’s more memorable than my previous name (Boka Esquina), plus it sounds less “hip hop” in a way, it even makes me feel less constrained to always do rap.

I feel freer to take this project to other genres and other worlds.

As for my character, I don’t know… I don’t think I’ve ever really thought about building a character, and I’ve always tried to be myself. Even though this has necessarily been contradictory, a bit deceitful and at the same time very real, I prefer to reflect my own personality and who/what/how I am, rather than define a fixed character.

How would you describe your music?

I think that’s kind of what my story is about. If you imagine music made by a cheeky, hip hop little girl, who used to be a naughty, sneaky little jackal, who’s now in the middle of a hormonal transition and has had experiences of both the streets and comfort, you’ll get what I do.

The truth is, I’m at a point where I want to redefine my direction and reimagine my music. For a long time, I codified it around vocabularies like boom bap and 90s rap. Today, I want to focus not on musical language, but on emotional language.

I want my music to be the music of a sentimental hoodlum, a big-assed scum with a big heart.

And I want it to be hip hop, trap, chicha, huayno, layku-layku, afrobeat, reggaeton…. It’s the music that will decide what it always wants to be.

How do you write your lyrics and what is your artistic process?

I usually write to a beat I have on my computer. I spend a lot of time creating instrumentals, then, when I have time, I smoke Cheese, sit down and listen to my beats. Sometimes I freestyle over them or try out lyrics I’ve written. That’s when a whirlwind begins where beat, music, lyrics and flow start to interact until they become one. Sounds good when you put it like that hahahaha.

But I’m not really the kind of artist who writes lyrics and then makes a song out of them, or who finishes a song and then makes the lyrics. In my process, one is always linked to the other. More and more, I like my lyrics to be like chords or arrangements of the song, and less like a text.

Which song(s) are you most proud of so far?

Hmm, that’s hard… Among the ones that have been released, I’d have to say “Trans Piketera”. It’s the first song I mixed and mastered myself. And for the video, the team went crazy and we managed to make something very beautiful, with all the girls from Casa Trans here in La Paz, with incredible costumes and artistic work…

Among the songs that haven’t been released yet, there are a few that I love and often listen to on a daily basis. And I’m really looking forward to releasing them.

Are you connected to the Bolivian hip hop scene? If so, what’s the female rapper and queer scene like there?

Yes, I think I’m connected to that scene. Between 2021 and 2023, my first and most important community was the hip hop scene. There are still a lot of people I love, who give me a push, whose life and work I also tremendously admire. We’ve even managed to organize some memorable events and workshops, and I’ve given rap lessons to children….

Now that I’m involved in other things, we no longer have the same proximity or trust with the movement. But that’s okay, like all friendships and relationships, it evolves over time, it grows and fades.

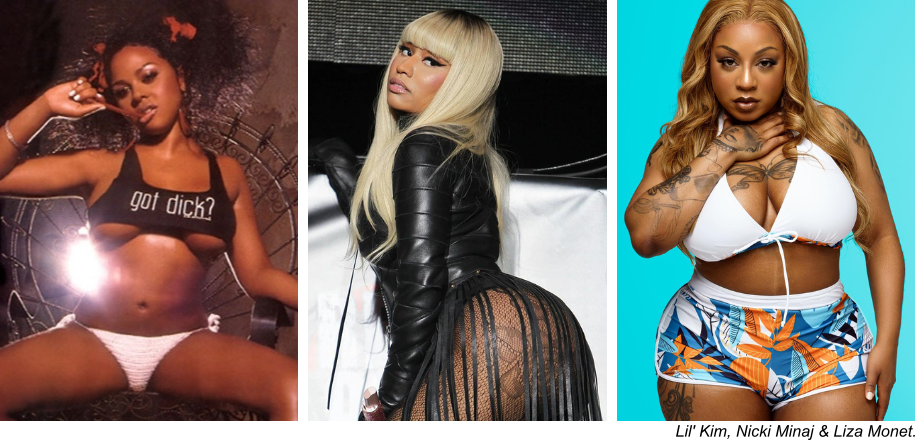

The “female” rap scene exists and stands up for itself, we’re not stupid. But it wouldn’t be fair to deny that the attention and spotlight is still directed at male MCs. I think we girls have had to step in and assert ourselves on this scene. There isn’t really a “female” rap scene per se. There is a rap scene, and if you’re a girl and you want to exist on that scene, you’re going to have to work hard.

You’ve got to get out there and show what you can do, defend yourself on paper and on the mic.

And it’s good that it’s like that, because it’s life here too, it’s the streets, work, family, business, parties, love, everything. And yes, you can talk about feminism and deconstruct expectations of artists and the world of hip hop, which is very chauvinistic… Or we can swallow the venom, become immune, rap even better and break everything. And be envied. And tell yourself that this scene is sexist because the industry is, not hip hop.

There’s no such thing as queer rap. There are queer rappers, dyke MCs, lesbian MCs, bi MCs. I carry all the trans representation in rap, that’s just the way it is. But I think the queer rap scene is still very much a European thing.

How do Bolivian audiences respond to female rappers?

They’re a mess. Between boys, they just watch, and when a girl comes along and raps better or in a more interesting way than their little street rapper pamphlets, she’s either booed or respected.

One side of the hip hop community is based on support and respect, just as another side is based on distrust and mistrust.

“Who the hell are you? I’ve never seen you in my neighborhood”, and they’ve already ignored you.

I won’t deny that I criticized Alwa‘s work at first, but now that she’s done so much in the field of education, that she’s become known, it allows her to perhaps better support herself or her family. She’s doing a lot for Bolivian “female” rap, and she’s a very dear friend, very talented and very sincere. She gets a lot of hate from the community, because she’s famous and because she wears skirts.

My friend from Cochabamba Kanto Tika Nina, who is also very strong, has also been ignored because she’s a girl who sings about killing macho men and being aggressive.

With me, it’s the same thing, “oh no, this girl is talking about being trans to become famous and make money, that’s all she wants”.

There’s a predisposition to always see vice, deceit and greed in Bolivian female rappers.

People don’t trust our authenticity and the fact that our music also comes from our reality. But they can suck our tits. I’m vicious, cunning, so what? In the end, Alwa breaks everything and I’ll break everything too. Little girls are more awake and work harder, because that’s what’s required of us, and that’s clearly what’s going to give us our lives back too.

As an artist, what have been or are the main obstacles you face?

Money is always an issue. Thanks to a combination of privilege and hard work, I’m lucky enough to be able to do a lot of things myself. I know how to make beats, mix and master. That saves me money.

But to make music videos, if I want them to reach the professional level we have to demand of ourselves to develop the Bolivian industry, you need money. What’s more,

coming out as a young trans woman and rapper also sometimes means coming up against a lot of transphobic and transmisogynist views.

But I don’t mind.

For me, I think the most difficult thing is the same as for all the other Bolivian MCs and all the other independent artists here. There’s no industry in Bolivia. And I don’t believe in the little speech that the state should come and invest in art, that the government should give us a hand and a bit of money, because we’re not babies.

The industry ceiling is very low, and it’s very difficult to break through.

There are no producers willing to invest, there are no record companies, none of that.

Today, we’re in 2024 and we can make a name for ourselves thanks to TikTok. We can also make a name for ourselves on the local underground scene, which is very lively. But here, the level of talent and hard work is very disproportionate compared to the level of artistic opportunity.

What are your upcoming projects?

I’ve finally released my latest rap mixtape RAPPASMUT’I and now I want to move on for a while. I’m working on some trap songs that I think will end up being the first “real” EP of the Hyena project.

I’ve also got an old school rap EP with my friend Dechope, a mixtape with my best friend Diva Virtual and a few loose tracks that I don’t know what I’m going to do with. But it’s going to happen fast, because I’m anxious and impatient to work.

What do you need today to develop your projects to the full?

Clarity and wisdom. I need more faith in my project and my message, because I sometimes have bouts of impostor syndrome, and I have to fight these thoughts. I also need security and well-being.

At the end of the day, my most important project is my transition, and to make the music I want to make, I have to be the person I want to be, and that’s not at all easy. After that, if I have my bike, good headphones and time on my hands, I think I’m capable of many things.

Find Kiya on Instagram, TikTok and YouTube.

© Radhi Gutierrez