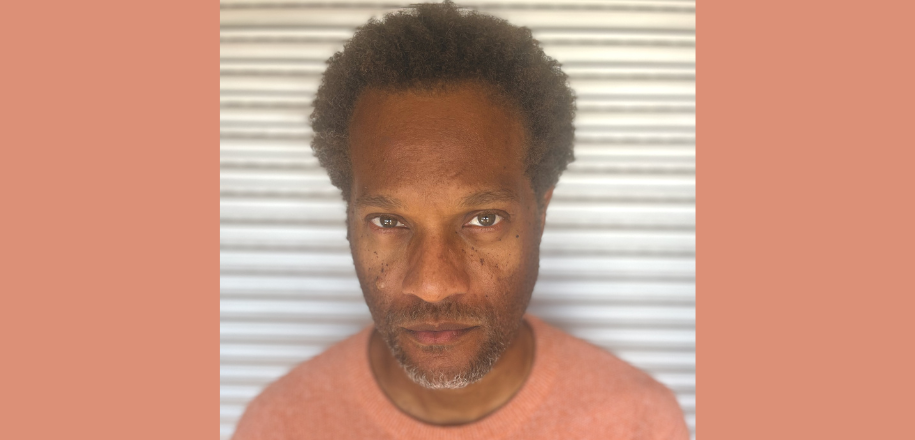

The award-winning British poet/rapper/poet/playwright/novelist Kae Tempest releases the album Let Them Eat Chaos. Madame Rap met them in Paris to discuss feminism, hip hop and writing.

How and when did you discover hip hop music?

I think I was about 12 or 13 when I fell in love with it. I always listened to music, but the lyrics in music were the thing that really touched me. And I used to read a lot of books for all my life. Lyricism was very exciting. Hip hop is this dominant social, cultural, political force, it’s a huge movement, it’s 50 years old at least. It’s no surprise that South London kids are gonna find their way into hip hop. At the time, it just felt like a kinda living breathing thing.

The first rappers I really fell into were Pharoahe Monch, Guru from Gang Starr, A Tribe Called Quest, Gravediggaz… That was actually Gravediggaz that was me. Too Poetic from Gravediggaz. I learned everything that a rapper could do from listening to him. And then Lauryn Hill, Bahamadia, Nas, Biggie and Big L. And then I learned more about what was happening in the UK. There was a guy called Chester P from Task Force and a guy called Skinnyman. I was like 15 by this point. I was just listening, watching and waiting for my turn really.

You’re a rapper, a spoken word artist, a poet and a playwright. Words are central in your work. What is your writing process? Do you have any rituals?

It depends. If I got a big deadline and something I need to finish, then it’s just to start and do it. I guess there are little rituals that you use to try to get into that space that you’re not in instinctively. Even just picking up that pen, there’s something powerful in that. Because I spent more time in my life looking at my hand with a pen in it than not.

I write with a pen in my notebook for the first draft. It’s better for my ideas because handwriting is connected to memory. So by the time you’ve written a lyric by hand, you’ve probably memorized it. Then I type the second draft and then work from the manuscript for the third, fourth, fifth draft. But the initial idea is always with a notebook.

Your new album Let Them Eat Chaos has something very dark, melancholic and introspective but also very hopeful and oneiric. What was your state of mind when you wrote it?

It’s about trying to get to the root of what might be keeping people awake at night. Who is awake at 4:18? It’s the question that leads you to the characters. Then obviously, my state of mind is all over the record. Whatever I was going through in the particular moment of writing. I think it’s quite present in the description of the characters but also in the grand epic way it begins in space.

My mind is constantly trying to get out of this tunnel vision and look up and see the world again. I’m glad you said it feels hopeful as well because I think it is a positive record.

Would you say it is a political record?

I think it’s impossible in 2016 to make a record that isn’t engaging with the times and the crisis that we’re in. Knowingly or unknowingly, everybody who is creating work is cyphering this stuff. I never set out to make a political statement in my work but of course politics is in me. I don’t accept any label. I’ve been trying really hard for a long time to show people that labels are constantly unsatisfactory.

The fact that I work across so many different forms means that you cannot apply a label, it doesn’t fit. This is part of my whole thing. The more that we reduce and minimize ourselves, so that other people can understand us, the more that we reduce others and minimize other people, so that we can understand them, the further away we get from actually being able to understand anything.

Especially when it comes to creative ideas, which begin in such a vast spaces. If you call yourself a political artist, or a rapper, a poet, or a novelist, then you’re not listening to the idea.

London is a recurring character in your work, but you seem to have mixed feelings for this city…

It’s home, it’s where I grew up. I never left. Lots of people leave where they’re from to find where they are. But I felt so rooted to that place that I didn’t need to go anywhere. But London is also full of pain.

There is a lot of reminders, of pain as well. But at the same time, it is a beautiful terrifying magical place. It’s in me but I feel like I need to be somewhere else. For the first time in my life, I feel like I need to leave. I wanna go to the Pyrenees, the mountains, the wolves, the sky. Anyway, I just thought of it today. I’m not actually gonna leave London, obviously!

In 2013 you won the Ted Hughes award for your work Brand New Ancients. What did this institutional acknowledgement change for you?

I like to think it doesn’t change much, but of course it does. For ten years, I was desperate to be heard. I couldn’t work out why I couldn’t get the gigs I wanted, I couldn’t get a record deal, I couldn’t get published. I was like burning up with fire to make a move but didn’t know how to make a move. I was working all day in schools, teaching lyric workshops and I was doing spoken word gigs in the early evening, and then gigs with my band. I was working every minute of the day and I wanted to be validated in a way. To be completely honest, it is much easier to say this stuff doesn’t matter once it’s happened to you. Before I won that award, there was not a chance for me winning a poetry award.

I wasn’t even gonna go to the ceremony. I spent the day in a women’s prison in Holloway, doing workshops with these women, with a play that I’d written. It was a serious day. I was working with these inmates, I was being shown the maternity of the prison, which is where the women are going to jail pregnant, they have their baby and after six months the baby is taken into care. And then I left to go to this fucking award party in a posh part of town, white wine and lots of fucking bullshit and I won this fucking poetry price. I just didn’t make any sense.

And then, I got all this attention from the poetry establishment, which I didn’t want and wasn’t really ready for. But actually, it begins to feel really exciting to imagine a whole lifetime of improving as a poet. This is important to me. It was a victory, not just for me, but for everyone who is rapping or doing spoken word.

Have you ever been discriminated against as an artist?

Of course. But I think it’s probably more important to say what a blessing it is to have the female perspective, the female courage, the female power and the female drive. It’s important to pay attention to the positive. I found the resilience that you have to have. It teaches you how to be sure of yourself, because nobody else is very sure about you.

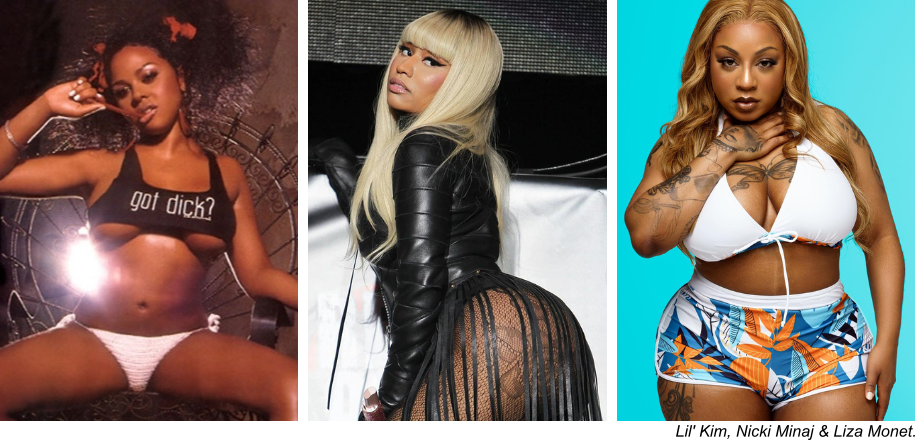

Hip hop is considered to be the most sexist music. What do you think about that?

When I was young, hip hop was everything to me. I was moving in that culture and I just absorbed it. At a subconscious level, I stopped hearing the misogyny, the homophobia… I was so in love with the art form that I stopped hearing it. I didn’t think all that stuff applied to me, even though I could hear rappers talk about women in ways that I found deeply upsetting.

As I got older, I realized that one of the most important teachings for me was authenticity. And for me being real with myself, I can’t just sit there and dismiss this stuff. And then I realized an important thing for me to do was make myself visible and make myself heard on a way that goes against everything that’s being talked about a woman’s place, a woman’s role. By getting up and getting on the mic and not looking sexy or stupid or not trying to suck anyone’s dick, and just wanting to speak about serious stuff, this was a way for me of resetting the balance a little bit.

The flipside of that is that if you’re not part of the culture and you look from the outside and judge it as misogynistic, I don’t really need to have that conversation with you because there are so many subtleties that you’re missing about the form and the culture anyway. If you’re gonna dismiss something as important and empowering and as righteous as hip hop culture and music, it’s not my job to educate you. There is a problem but you have to be in it to understand the nuances of it.

I was just this little queer and weird kids, all my friends were just men and I just dealt with it. I know how much a performance it is. It’s a kind of bravado and adolescent thing and I know the reality of how these men actually engage with their mothers or their sisters is very different. So I kind of know it’s no real threat, it’s a dance, an ugly dance, they’ll grow out of it. They just need to fall in love as well!

Do you consider yourself a feminist?

I don’t consider myself, I’m just making the work. I think it’s probably important to say I believe in true equality.

What are you listening to these days?

Loads of stuff. There’s a rapper called Trim and his album is wicked. There’s this Rn’B singer called Rosie Lowe, she’s produced by this guy called Dave Okumu, who’s amazing. He’s in a band called The Invisible in the UK, he’s really cool. I listen to Pharoahe Monch all the time, Mos Def or Yasiin Bey, Little Simz… There’s a really cool band called Paranoid London, they’re like this dirty, minimal, kinda lie disgusting house. I love it!

What are your upcoming projects?

I’m working on a play but I don’t know when it’ll be finished. There’s also a new book of poems… I usually have four or five projects happening at the same time. They kinda inhabit the same space. Now I’m touring with this album and will be doing this for a while, but I don’t stop working on ideas just because I’m not physically working on them.

I’m also working on a new album slowly but I’ve been in a real rush to get to this point for a long time. I spent five years non-stop trying to get here. So the next project is gonna be a bit slowler.

Find Kae Tempest on their website, Facebook and Twitter.